您的购物车目前是空的!

How to Be a More Detailed Writer .Details can transform a dull passage into a gripping story, or turn a weak argument into a persuasive one. They breathe life into descriptions, changing a simple “worn pair of sneakers” into “a pair of Air Jordans with frayed laces and tread long-since worn away.” While fiction and literary non-fiction often gain the most from vivid detail, you can enhance any type of writing—whether through careful research, cutting unnecessary adverbs, or engaging the senses of taste, smell, and touch.

Method1 Adding Details to Your Writing

1. Show, Don’t Tell

The golden rule of descriptive writing is to show your reader what’s happening instead of simply telling them. Don’t just say a character is angry—demonstrate it with clenched jaws, sharp tones, or stiffened posture. Likewise, don’t write that a building is “run down.” Instead, describe the broken windows, peeling paint, and the pervasive stench of urine. The power lies in details.

Example: Alexander McCall Smith, in The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency, describes a mud hut not as just “a house,” but with images of faded wall paintings and bare earth walls that carry history in every detail.

👉 Learn more about “Show, Don’t Tell” techniques.

Subheading: Evoke Emotion Through Action and Setting

2. Focus on Key Details

Too many details can overwhelm your reader, slowing pacing or clouding an argument. The art lies in selecting only the most precise details that illuminate a character, theme, or mood. Ask yourself: Why am I including this? Every detail should serve the story or argument.

Example: In The God of Small Things, Arundhati Roy captures the oppressive heat of a church not by listing everything in the setting, but by letting the curling lilies, a dying bee, and a trembling hymnbook reveal Ammu’s fragile emotional state.

👉 See Arundhati Roy’s writing style analysis.

Subheading: Choose Precision Over Excess

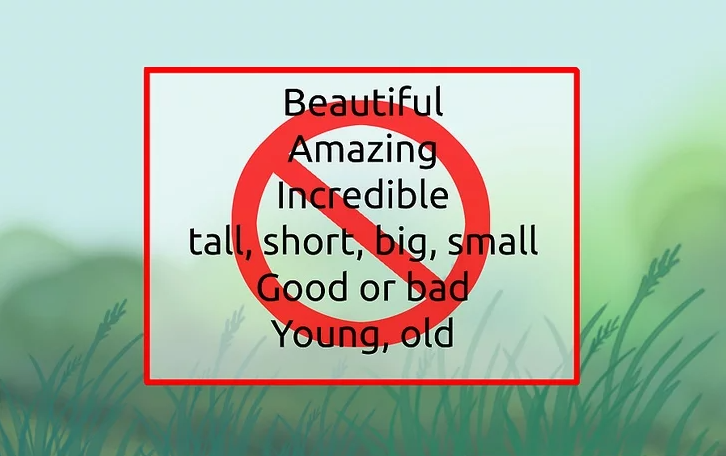

3. Avoid Empty Descriptive Words

Words like beautiful, good, amazing, or delicious may sound descriptive, but they don’t show anything. Instead of vague adjectives, give the reader sensory images that spark imagination. Replace “the meal was delicious” with the specifics of its flavors, textures, and aromas.

Example: Instead of calling Shakespeare’s Hamlet “a good play,” a stronger thesis might argue that Hamlet’s noble intentions are overshadowed by his destructive choices, making him morally similar to Claudius.

👉 Read more about avoiding weak adjectives.

Subheading: Replace Vague Words With Sensory Clarity

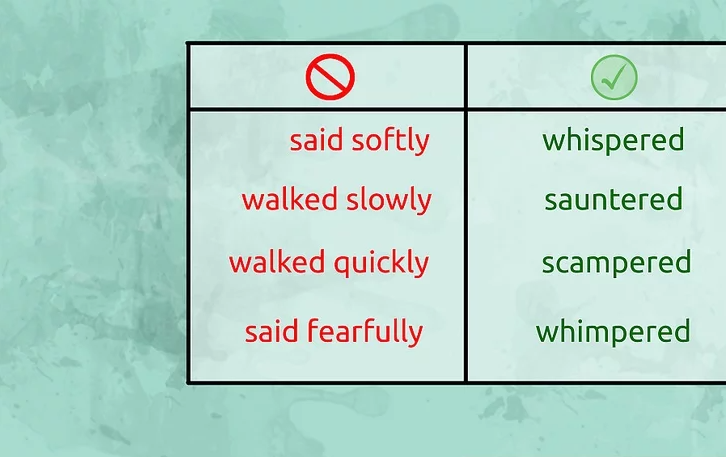

4. Cut Back on Adverbs

Stephen King famously warned: “The road to hell is paved with adverbs.” Adverbs often signal weak verbs or lazy descriptions. Instead of writing “walked quickly,” use “hurried” or “scampered.” Instead of “said softly,” choose “whispered.” Replace vague adverbs with stronger verbs or contextual actions.

Example: Rather than “she walked softly,” describe her intent: She tiptoed past the guard, each floorboard creak sounding like thunder in her ears.

👉 See Stephen King’s advice on adverbs.

Subheading: Replace Weak Adverbs With Strong Verbs

5. Engage All Five Senses

Sight alone is never enough. Writing becomes vivid when you draw on smell, taste, sound, and touch alongside visuals. Sensory writing places readers directly in the moment.

- Smell: Patrick Süskind’s Perfume depicts the stench of sweat, rancid cheese, and sour milk with overwhelming realism.

- Taste: A simple gulp of briny seawater can carry more impact than a paragraph of visuals.

- Sound: Robert Frost’s description of cracking branches compares forest sounds to rhythmic drumming.

- Touch: E.B. White captures discomfort in a child’s icy, wet swim trunks in Once More to the Lake.

👉 Guide to using sensory detail in writing.

Subheading: Create Immersion With Sensory Language

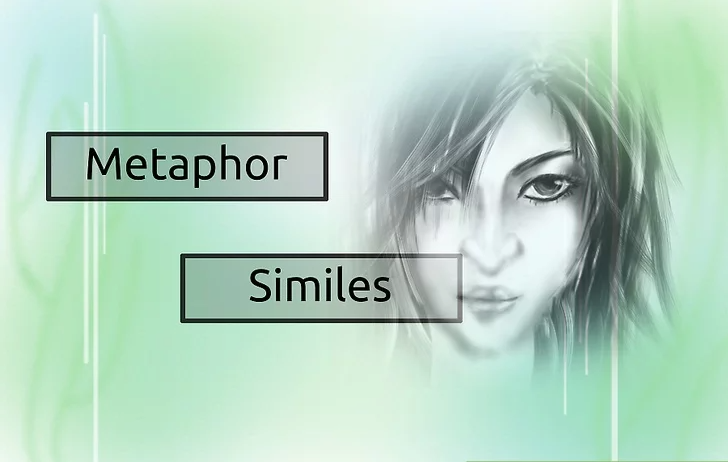

6. Use Similes and Metaphors Wisely

Similes (“like” or “as”) and metaphors (direct comparisons) can add brilliance to your writing, but overuse or cliché can weaken prose. Keep comparisons fresh, clear, and consistent.

- Good Example: Shakespeare’s “All the world’s a stage” elegantly reframes life itself.

- Bad Example: Mixing metaphors (“the ship of state on its feet”) confuses rather than clarifies.

- Best Practice: Use metaphors that evoke tangible sensations, like Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ “The water made a sound like kittens lapping.”

👉 Learn the difference between metaphors and similes.

Method2 Researching for Greater Detail

1. Start with General Background Research

Every strong piece of writing begins with a foundation of background knowledge. What this means depends on your genre:

- Fiction: Learn about your character’s world—such as their career, culture, or setting—without obsessing over minor facts.

- Academic Non-Fiction: Familiarize yourself with the key literature in your field. Your work should engage with and respond to previous scholarship.

- Professional Writing: Whether drafting a pitch or legal pleading, research the critical details first to frame your argument.

👉 Guide to background research in writing.

Subheading: Build a Knowledge Base Before You Write

2. Use the Internet as a Starting Point

The internet can be a valuable launchpad for research, but it should never be your final stop. Wikipedia and similar resources provide useful overviews, but always verify details using at least three independent, credible sources. Prioritize peer-reviewed journals, university press books, and government publications for trustworthy information.

Subheading: Balance Online Sources with Scholarly Works

3. Begin Writing Before You Finish Researching

Don’t wait until you’ve learned everything before putting words on the page—you’ll never start. Instead, begin with the basics, sketch an outline, and identify gaps as you write. This allows you to research with purpose, avoiding wasted time on irrelevant details.

👉 Why writers should draft early.

Subheading: Write and Research in Tandem

4. Use Bibliographies and Notes to Find More Sources

When a book or article cites an intriguing fact, track it back to the original reference. Following bibliographies leads you to primary sources, which often hold deeper insights and fresh material for your own interpretation.

👉 How to trace citations effectively.

Subheading: Let References Guide You to the Originals

5. Make Friends with Librarians

Librarians—especially in universities—are powerful allies in your research journey. They can point you to specialized databases, hidden collections, and sources you might never uncover on your own. Plus, they are trained professionals who genuinely enjoy helping researchers.

👉 Why librarians are your best resource.

Subheading: Leverage Expert Guidance

6. Keep Track of Your Sources

Meticulous record-keeping is essential. For non-fiction, accurate citations establish credibility and protect against plagiarism. Even in fiction, knowing where you found information allows you to revisit details later. Use citation managers like Zotero or Mendeley to organize your references efficiently.

👉 Best citation management tools.

Subheading: Stay Organized and Avoid Plagiarism

Method3 Creating More Detailed Fiction

1. Move Beyond Physical Appearance

Characters are more than just faces and hair colors. Their thoughts, actions, histories, and the way others react to them often make the strongest impressions. Sherlock Holmes, for example, is remembered less for his looks and more for his genius, aloofness, and reliance on drugs. Try showing personality through:

- Other characters’ reactions (“Every eye fixed on Esmeralda as she entered the room.”)

- Personal history (“He once ate an entire boar in a single sitting.”)

- Movements (“She moved with the grace of a dancer.”)

- Defining features without overloading details.

👉 How to develop characters beyond appearance.

Subheading: Show Personality, Not Just Looks

2. Use Voice to Create Character

A character’s voice—the way they speak, think, and narrate—can be their most defining trait. Consider Balram Halwai in Aravind Adiga’s The White Tiger, whose witty and biting commentary sets the tone of the entire novel. A distinctive voice makes a character unforgettable.

👉 The importance of voice in character writing.

Subheading: Let Dialogue and Tone Shape Identity

3. Keep Descriptions of Settings and Objects Short

Over-describing slows down pacing and dilutes impact. Instead, highlight a few striking details and let readers fill in the blanks. Erin Morgenstern’s The Night Circus demonstrates this with compact yet dazzling descriptions, such as a clock with turning pieces, carved flowers, and pages in miniature books.

👉 Tips on concise description in fiction.

Subheading: Use Precision, Not Overload

4. Use Real Place Details Judiciously

In genres like historical fiction, setting often functions like a character. But balance is crucial: too many details overwhelm. Instead, choose sensory images (gaslight circles on cobblestones, bread mixing with river stench, church bells across Paris). Place names and foreign words also ground readers in time and place—as James Clavell does in Shōgun with Japanese terms like “hai” and “tomodachi.”

👉 How to write setting effectively.

Subheading: Anchor Setting Without Overwhelming Readers

5. Describe Through Absence

Sometimes, what’s missing tells the deeper story. A smiling woman with lifeless eyes, a forest without birdsong, or a circus stripped of color can evoke mystery and unease. In The Night Circus, Erin Morgenstern conveys wonder by describing what isn’t there: no crimson tents, no golden banners—only stark black and white.

👉 Literary technique: describing through absence.